Life & Work

Montreal potter Rosalie Goodman Namer played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Canadian field of studio ceramics. She was a central contributor to an ebullient cultural context propelled by the renewed enthusiasm for craft that was widespread in the second half of the twentieth century, both as a creator, teacher, and clay researcher. Through the 1960s and 1970s, Namer produced tens of thousands of pots from her studio in the West Island of Montreal while teaching as head of the ceramics department at McGill University's MacDonald College. Namer’s ceramics practice was rooted in a profound affinity for the Canadian landscape: not only did her work emphasise the richness of local clays through sophisticated glazes and extensive material research, but she also facilitated intimate relations with people across Canada through the production of functional everyday wares.

Namer was a staunch advocate for the recognition of the professional status of craftspeople, and was instrumental in research into lead poisoning, contributing to "Earthenware Containers as a Source of Fatal Lead Poisoning," a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1970. Considered one of the strongest potters in Canada, Namer received funding from the Canada Council for the Arts to conduct extensive experiments on various Canadian clays in 1968 and was awarded the 1970 Grand Prix d'Artisanat du Quebec. Her pottery also resonated outside Canada, as she participated in numerous international craft exhibitions.

1. Early Years

Born Roslyn Goodman July 19,1925 in Montréal, Canada, Namer was the child of Moses Goodman (b.1895 Suceava, Romania) and Beyla “Bessie” Schrier (birthdate unknown, Volochis'k, Ukraine). Her parents immigrated to Canada at the turn of the twentieth century as part of a wave of East-European Jewish migration fleeing pogroms and antisemitic persecution. Like many Jewish immigrants arriving in Montreal at this time, Moses Goodman worked in the textile industry, as a partner of Goodman Brothers, a retail company supplying fashion houses in the northeastern United States. Rosalie was the middle child of three sisters, the eldest Mildred Goodman, an internationally recognized violinist and influential member of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra from 1955 to 1988.

![]() Namer dressed as cupid, Saint-Faustin-Lac-Carré, Québec, circa 1929

Namer dressed as cupid, Saint-Faustin-Lac-Carré, Québec, circa 1929

Namer grew up on Montreal’s Villeneuve and Plantagenent streets and completed her secondary education at Strathcona Academy, a predominantly Jewish high school under the jurisdiction of the city’s Protestant School Board. She married Norman Nemerofsky in 1945 immediately after the end of the Second World War. They had two children: Michael in 1945 and Gwenda in 1952.

During Namer's early life, in the 1930s and 1940s, a growing antisemitic climate spread across Canada, particularly in Quebec,a province highly influenced by the Catholic church. Jewish families faced significant restrictions and discrimination in universities and governmental institutions. Many influential figures openly expressed anti-Jewish sentiment in newspapers and in Parliament. Although after the Second World War, verbal anti-Jewish attacks were prohibited, covert anti-semitic violence and discrimination continued to be present in Canadian society. This cultural context prompted Rosalie to modify the family's last name from Nemerofsky to Namer in the hopes that her children would have a less legibly Jewish name and thus experience less prejudice.

![]()

Namer with Norman Nemerofsky in Montreal, 1943.

2. The 1950s: Education and Craft Awakening

Namer's first contact with the world of art was through painting. Showing interest in visual expression, she studied with Arthur Lismer, the celebrated English Canadian painter, landscapist, and member of the Group of Seven. In 1945, Namer entered Sir George William College (now Concordia University) to study painting and sculpture. While she enjoyed her two years in the department of Fine Arts, Namer found the disciplines of painting and sculpture too elitist and isolating, and gallery and museums spaces too hermetic (Fisette, 1974). She wished to establish more intimate contact with the public through the creation of affordable and functional objects that people could use daily. This key realization grounded her growing attraction to craft and would follow her throughout her career.

After experimenting with other means of artistic expression, Namer settled on the medium of pottery. Eager to develop her skills, she enrolled in the first season of Gaetan Beaudin's influential pottery summer school in North Hatley in 1954. Studying with Beaudin, who was at the time considered as the father of studio pottery in Quebec, Namer learned about different types of stoneware glazes (Crawford, 2005). More importantly, during these three months of intense production, experimentation, and communal exchanges, she met a number of accomplished potters and joined a vibrant craft community.

After completing her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts of Montreal in 1956, Namer enrolled in a ceramic certificate at Montreal's Institute of Applied Arts with the intention of becoming a professional potter. She was described as one of the most passionate and "voracious learners" (Crawford, 2005). The Institute was led by potter Maurice Savoie under Jean-Marie Gauvreau's direction. Having studied ceramics in France and Italy, Savoie and Gauvreau promoted a European approach to ceramics. The department would provide a very practical education, focusing on established production techniques such as mould-making (Crawford, 2005).

The guidance of Gilberte Gambier Normandeau, the Institute's resident glaze technologist, was influential on Namer. Normandeau set up a chemistry laboratory where students could experiment with different clay and glazing technologies. Namer demonstrate a strong interest in glazes, so was given permission to work at the Institute an extra year, using the laboratory for self-directed study and experimentation upon the condition she shared her glaze recipes with the ceramic department. This privileged access to materials and equipment helped Namer develop a solid knowledge of glaze chemistry, and she was soon recognized as the Institute's resident glaze expert. By the time she completed the four-year program in 1961, Namer had established a professional studio practice. She began exhibiting her pottery next to her teachers in various provincial and national contests and exhibitions and was no longer considered a student but an experienced and skilled craftsperson.

The training Namer received at the Institute of Applied Art provided her with a solid technical and theoretical foundation, however the department's Eurocentric, conservative approach to ceramics did not significantly engage with emerging international craft scholarship and practices. In the 1950s and 1960s, two main attitudes toward pottery teaching prevailed in Quebec. Besides the Institute's European-based theoretical education, a younger generation of potters, of which Namer was part, were influenced by Asian, specifically Japanese, craft philosophy and praxis. This movement promoted a more experimental approach "to material and processes" and a ceramic practice that was "visual, sensual and spiritual rather than technical" (Crawford, 2005). It was founded on values of simplicity, humility, utility, and beauty, and challenged the European academic’s emphasis on technical prowess.

By being educated entirely in Quebec, Namer diverged from many of her peers who went to France, Italy, or Japan to study ceramics. This did not, however, stop her from experimenting with a wide range of international aesthetics and techniques throughout her studies. Namer's education was not limited to her certificate at the Institute of Applied Arts: she also read many works of craft literature and craft theory. Like other Canadian potters of her generation, she was inspired by the scholarship of eminent British potter Bernard Leach and his 1940 publication A Potter's Book. Namer also often made constant reference to the 1963 essay "Seeing and Using: Art and Craftsmanship" by Mexican poet and writer Octavio Paz. More importantly, she broadened her horizons on craft through collaborations and exchanges with potters from around the world.

3. 1958-1978: Teaching at Macdonald College

Namer was recognized across Canada as an exceptional, rigorous, and devoted teacher and mentor. She played a key role in the establishment of studio ceramic education in Canada through her work as head of the ceramics department of McGill University’s MacDonald College. She began teaching in 1958 while still a student at Montreal's Institute of Applied Arts. She was first approached by a local pottery club, The Claycrafter, to teach afternoon workshops at Macdonald College. She initially intended to teach there for only two years but was then hired as head of the ceramics department, a position she would occupy for eighteen years. Before her arrival, the department had been closed for twenty-five years, requiring Namer to work considerably to modernize and restore the outdated equipment. She built the department's kiln herself and put in place a fully equipped studio that allowed her to instruct up to eighty-five students a week (Wells, 1966).

![]()

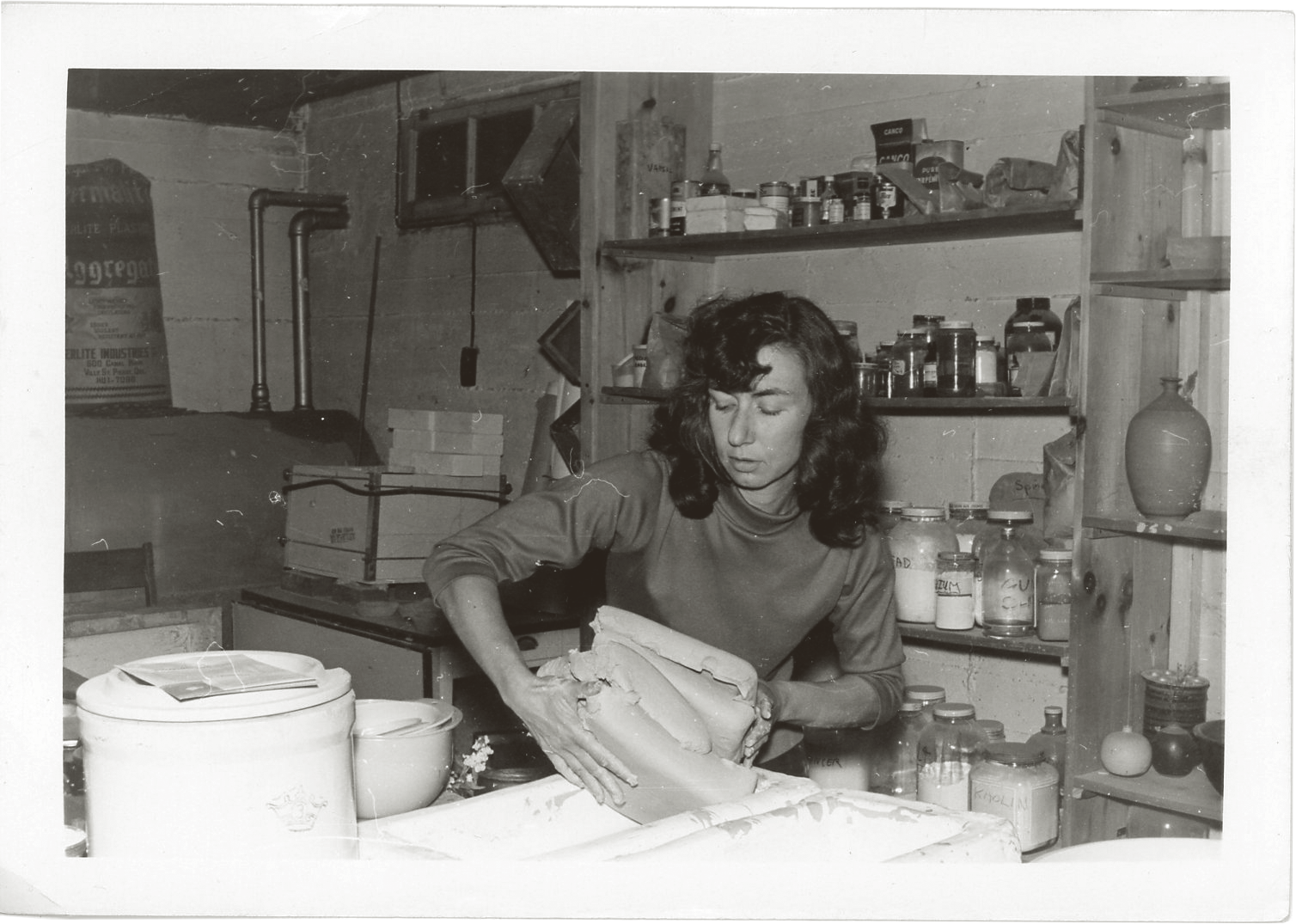

Namer working in the MacDonald College pottery studio, circa 1965.

The quality of instruction in Namer's department rapidly gained a reputation in Montreal's craft community. Her course attracted a diversity of students: "business and professional men," as well as "professional women, housewives, and society matrons" (Rochester, 1963). Moreover, Namer taught university students and teachers-in-training. Many of her students, such as Brenda Sullivan, Joanne Cunnington, Phyllis Atkinson, and Eileen Reed, became influential contributors to the field of studio ceramics in Canada. Ceramics was taught in her class as a profession and not solely as vocational therapy. Notably, Sullivan describes how Namer "taught [her] to study as a professional potter, not as a hobbyist," and "instilled a particularly strong work ethic." Under Namer, "serious education was possible;" Namer's courses were considered "the only suitable [ones] in Montreal for those interested in becoming professionals"(Crawford, 2005).

Her students received a thorough education. They would learn to prepare clay in its raw form and were encouraged to experiment with various materials sourced across Canada. They would also learn about the use and maintenance of technologies and equipment. One of her courses taught students how to build kilns. In this way, Namer would encourage students to establish their own independent pottery studios. She also offered more advanced classes where students could deepen their knowledge of glazing techniques and technologies. As opposed to most of the ceramics departments in the country, students learned to prepare glazing recipes instead of using commercially prepared ones (Rochester, 1963).

Namer's mentoring was not limited to Macdonald college. She shared her expertise in a series of seminars organized by the Montreal Potters' Club in the 1960s. Furthermore, she lectured at the Institute of Applied Arts for two years. She also led numerous workshops and worked as a consultant for independent ceramic studios across the country. Notably, she oversaw the construction of the kiln for the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and its ceramics studio at the end of the 1960s. She was invited by the new president Garry Kennedy "to lead the clay section (..) as a stoneware specialist," an offer that Namer declined because she felt the need, at this moment in her career, to refocus on her personal production: "I gave so much energy to teaching. The ideal way is to teach when you are old and tired, not when you are just starting out" (Crawford, 2005).

4. The 1960s: Emergence as a Professional Potter

The 1960s marked an epoch of intense and focused production in which Namer forged her identity and reputation as a craft professional. In parallel to teaching full-time at Macdonald College, Namer responded to a growing number of orders, sometimes producing “at least 300 hundred domestic articles every week.” To combine her teaching career and studio practice, she followed a demanding schedule. In her personal studio in the basement of her home, she shaped and prepared ceramics pieces and then brought them to Macdonald College for the firing and glazing using the department’s equipment before her classes began (Crawford, 2005).

Starting early in the morning and finishing late at night, "she was totally consumed by the world of pottery-making" (Crawford, 2005). For Namer, "If you are a producing potter instead of a past-time potter, you [need to] build your life around it." She also expressed how the nature of the medium demanded that it become "a way of life": "You can't start some pieces and then run off for a holiday in the country." Gaetan Beaudin described Namer as “the hardest worker he ever knew” while Gail Crawford characterized her as a “high powered intense woman” (Crawford, 2005).

Namer started participating in numerous national craft exhibitions at the beginning of the 1960s. Her work stood out for her skillful use of the material and her mastery of glazing. In 1962, her Toronto's Galerie Artisans mounted Namer’s first solo exhibition. The same year, she participated in the 22nd Ceramic National exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York. This first exhibition in the United States allowed her work to gain international attention. She then participated in craft exhibitions in Berlin, Germany and Faenza, Italy. In 1963, she won the first prize of the Association Professionelle des Artisans du Québec for her work presented at the 8th Edition of the Palais du Commerce’s Craft Fair. Seeing her pottery, MacLean's journalist Gilles Derome described Rosalie Namer as "one of the most solid potters in Canada" (Derome, 1964). This recognition launched her career and marked the beginning of her professional success.

In 1965, she acted as the chairman of the jury for the Biennale of Canadian Ceramic, where she and colleagues Robert Champagne and Yves Trudeau established the biennale's selection criteria and publicly discussed what they considered to be the direction of contemporary pottery. This experience consolidated her status as a leading figure in the Canadian field of studio ceramics.

Following these exhibitions and appearances, Namer received a growing number of commercial orders. While at the beginning of the 1960s she sold her work mostly to clients and galleries from eastern Canada, by the end of the 1960s, orders were placed from across the country; "[her] work [was] all spoken for." During this productive period, Namer worked swiftly and had one of Canada's most abundant and regular studio productions.

5. 1968-1969: Experimentations and Research

Namer was awarded a grant of $6,000 from the Canada Council for the Arts in 1968 with the purpose of conducting extensive experiments on Canadian clays. Up until that time, Namer worked with a sandstone sourced in Saskatchewan, but this clay became unavailable, and Namer needed to find a new supplier. A similar type of clay could be purchased in the United States, but Namer preferred to source her material in Canada. Indeed, through her craft, she wished to call attention to the rich clays of the Canadian landscape. Furthermore, she was not satisfied with the clays that available on the market and wanted to develop better options for Canadian potters. On the one hand, her research project responded to the need to source suitable and affordable clays in local deposits; on the other, it was fueled by a desire to experiment with new materials and to renew her craftsmanship. With this funding, Namer traveled to different clay deposits in the Canadian prairies and the Maritimes. She was particularly interested in white stoneware sourced from the Shubenacadie area of Nova Scotia and established a commercial relationship directly with the clay deposit.

She would present the outcomes of this research in two major Canadian craft exhibitions, Ceramique 69 and Dimension Canada, and, in a solo show at Montreal's Central d'Artisanat. Furthermore, in 1970, she was awarded the Grand Prix d’Artisanat du Quebec in recognition of her experimentations with Canadian clays. These three major exhibitions and this award marked the end of a prolific decade of production and experimentation and sealed her reputation as one of the strongest potters in Canada.

![]() Solo exhibition at the Central d'Artisanat, Montreal, 1970

Solo exhibition at the Central d'Artisanat, Montreal, 1970

In 1968 and 1969, in parallel to her project on Canadian clays, Namer also conducted an independent scientific investigation on lead glazes in collaboration with Dr. Ben Warkentin, professor of soil analysis at MacDonald College. Namer undertook this project after a child in Montreal died from lead poisoning: the young boy had drunk juice from an earthenware pot handcrafted by an amateur potter in Nova Scotia. When in contact with the juice's acidity, the container's glaze released soluble lead, which caused the fatal intoxication. Namer tested a series of twenty handcrafted and commercial pots that she suspected could represent public health hazards. She also reproduced common glazing recipes that used lead and experimented with their firing to analyze how their composition changed. She presented the results of her experimentations in an article entitled "Earthenware Containers as a Source of Fatal Lead Poisoning," co-written with Dr. Michael Klein, Eleanor Harpur, and Richard Corbin, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1970. Namer suggested a series of recommendations: the government needed to impose on craftspeople guidelines to ensure that all pots were safe for table use. She further recommended that only professionally trained potters with a good understanding of the chemistry of clay should be allowed to craft objects for table use and that pre-mixed glazes should be compulsory for beginners and amateurs. This research highlighted the scientific aspect of Namer’s career; she was recognized not only as a potter but also as an expert in glaze chemistry.

6. 1970s: Work at the Beaconsfield Studio

After her research in Nova Scotia and her scientific investigation into lead poisoning at the end of the 1960s, Namer felt she was spending too much time away from her wheel. The 1970s therefore mark a return to the studio and represent a period of maturity and prosperity for Namer. Her career was established, and her previous shows' success allowed her to secure clients and orders across Canada. For these reasons, she stopped participating in competitions and exhibitions to focus on what was most important to her: producing functional objects for the public.

![]()

Namer photographed by Richmond Jones in her Beaconsfield studio.

She built a studio in her home on the West Island of Montreal. Large windows, old wood furniture, and various plants transformed the pottery studio into an organic environment (Morency, 1970). The completely furnished workshop was equipped with a manual wheel and a large kiln "that can reach 200 degrees and receive up to 250 middle-size ceramic pieces." There was also a room where Namer prepared the clay and space for mixing and applying the glazes. This installation allowed her to produce hundreds of pieces per week.

7. Final Years

In 1978, at the age of 52, Namer suffered a spinal disc herniation that would forever alter the course of her life and work. The making of pottery is an intensely physical activity that over the long term has an impact on the potter's body. Namer worked daily with a manual kick wheel for over twenty years, an activity that involved persistent, repetitive movement, potentially creating the conditions for what became a sustained back injury. Numerous surgeries followed, one which led to the accidental puncturing of the cerebrospinal fluid sac surrounding her spinal cord, causing metastasizing inflammation of the fluid sac. In consequence, Namer developed arachnoiditis, a permanent, untreatable disorder which causes chronic and persistent pain, numbness, tingling, stinging and burning sensations along the spinal cord. After a series of unsuccessful surgeries in the 1980s that failed to relieve Namer’s pain, her physical condition made a return to the pottery studio impossible. This represented a dramatic turn of events that forced Namer to abandon a practice and passion that had been integral to her life for more than two decades.

Namer sold her pottery studio equipment and began experimenting with other forms of creative expression and mediums more adapted to her physical condition. She notably bought photography and print-making equipment. However, her chronic pain, more than a physical disability, deeply impacted her ability to create and develop a new artistic practice with these mediums.

![]() Polaroid self-portrait with aubergines, azaleas, and ficus, Beaconsfield, circa 1985.

Polaroid self-portrait with aubergines, azaleas, and ficus, Beaconsfield, circa 1985.

In 2006, after almost three decades of unsuccessful chronic pain management, Rosalie Namer travelled to Zurich, Switzerland, to seek physician-assisted suicide facilitated by the Swiss non-profit organisation Dignitas. She died on May 10, 2006, accompanied by members of her family.

Namer was a staunch advocate for the recognition of the professional status of craftspeople, and was instrumental in research into lead poisoning, contributing to "Earthenware Containers as a Source of Fatal Lead Poisoning," a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1970. Considered one of the strongest potters in Canada, Namer received funding from the Canada Council for the Arts to conduct extensive experiments on various Canadian clays in 1968 and was awarded the 1970 Grand Prix d'Artisanat du Quebec. Her pottery also resonated outside Canada, as she participated in numerous international craft exhibitions.

1. Early Years

Born Roslyn Goodman July 19,1925 in Montréal, Canada, Namer was the child of Moses Goodman (b.1895 Suceava, Romania) and Beyla “Bessie” Schrier (birthdate unknown, Volochis'k, Ukraine). Her parents immigrated to Canada at the turn of the twentieth century as part of a wave of East-European Jewish migration fleeing pogroms and antisemitic persecution. Like many Jewish immigrants arriving in Montreal at this time, Moses Goodman worked in the textile industry, as a partner of Goodman Brothers, a retail company supplying fashion houses in the northeastern United States. Rosalie was the middle child of three sisters, the eldest Mildred Goodman, an internationally recognized violinist and influential member of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra from 1955 to 1988.

Namer dressed as cupid, Saint-Faustin-Lac-Carré, Québec, circa 1929

Namer dressed as cupid, Saint-Faustin-Lac-Carré, Québec, circa 1929Namer grew up on Montreal’s Villeneuve and Plantagenent streets and completed her secondary education at Strathcona Academy, a predominantly Jewish high school under the jurisdiction of the city’s Protestant School Board. She married Norman Nemerofsky in 1945 immediately after the end of the Second World War. They had two children: Michael in 1945 and Gwenda in 1952.

During Namer's early life, in the 1930s and 1940s, a growing antisemitic climate spread across Canada, particularly in Quebec,a province highly influenced by the Catholic church. Jewish families faced significant restrictions and discrimination in universities and governmental institutions. Many influential figures openly expressed anti-Jewish sentiment in newspapers and in Parliament. Although after the Second World War, verbal anti-Jewish attacks were prohibited, covert anti-semitic violence and discrimination continued to be present in Canadian society. This cultural context prompted Rosalie to modify the family's last name from Nemerofsky to Namer in the hopes that her children would have a less legibly Jewish name and thus experience less prejudice.

Namer with Norman Nemerofsky in Montreal, 1943.

2. The 1950s: Education and Craft Awakening

Namer's first contact with the world of art was through painting. Showing interest in visual expression, she studied with Arthur Lismer, the celebrated English Canadian painter, landscapist, and member of the Group of Seven. In 1945, Namer entered Sir George William College (now Concordia University) to study painting and sculpture. While she enjoyed her two years in the department of Fine Arts, Namer found the disciplines of painting and sculpture too elitist and isolating, and gallery and museums spaces too hermetic (Fisette, 1974). She wished to establish more intimate contact with the public through the creation of affordable and functional objects that people could use daily. This key realization grounded her growing attraction to craft and would follow her throughout her career.

After experimenting with other means of artistic expression, Namer settled on the medium of pottery. Eager to develop her skills, she enrolled in the first season of Gaetan Beaudin's influential pottery summer school in North Hatley in 1954. Studying with Beaudin, who was at the time considered as the father of studio pottery in Quebec, Namer learned about different types of stoneware glazes (Crawford, 2005). More importantly, during these three months of intense production, experimentation, and communal exchanges, she met a number of accomplished potters and joined a vibrant craft community.

After completing her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts of Montreal in 1956, Namer enrolled in a ceramic certificate at Montreal's Institute of Applied Arts with the intention of becoming a professional potter. She was described as one of the most passionate and "voracious learners" (Crawford, 2005). The Institute was led by potter Maurice Savoie under Jean-Marie Gauvreau's direction. Having studied ceramics in France and Italy, Savoie and Gauvreau promoted a European approach to ceramics. The department would provide a very practical education, focusing on established production techniques such as mould-making (Crawford, 2005).

The guidance of Gilberte Gambier Normandeau, the Institute's resident glaze technologist, was influential on Namer. Normandeau set up a chemistry laboratory where students could experiment with different clay and glazing technologies. Namer demonstrate a strong interest in glazes, so was given permission to work at the Institute an extra year, using the laboratory for self-directed study and experimentation upon the condition she shared her glaze recipes with the ceramic department. This privileged access to materials and equipment helped Namer develop a solid knowledge of glaze chemistry, and she was soon recognized as the Institute's resident glaze expert. By the time she completed the four-year program in 1961, Namer had established a professional studio practice. She began exhibiting her pottery next to her teachers in various provincial and national contests and exhibitions and was no longer considered a student but an experienced and skilled craftsperson.

The training Namer received at the Institute of Applied Art provided her with a solid technical and theoretical foundation, however the department's Eurocentric, conservative approach to ceramics did not significantly engage with emerging international craft scholarship and practices. In the 1950s and 1960s, two main attitudes toward pottery teaching prevailed in Quebec. Besides the Institute's European-based theoretical education, a younger generation of potters, of which Namer was part, were influenced by Asian, specifically Japanese, craft philosophy and praxis. This movement promoted a more experimental approach "to material and processes" and a ceramic practice that was "visual, sensual and spiritual rather than technical" (Crawford, 2005). It was founded on values of simplicity, humility, utility, and beauty, and challenged the European academic’s emphasis on technical prowess.

By being educated entirely in Quebec, Namer diverged from many of her peers who went to France, Italy, or Japan to study ceramics. This did not, however, stop her from experimenting with a wide range of international aesthetics and techniques throughout her studies. Namer's education was not limited to her certificate at the Institute of Applied Arts: she also read many works of craft literature and craft theory. Like other Canadian potters of her generation, she was inspired by the scholarship of eminent British potter Bernard Leach and his 1940 publication A Potter's Book. Namer also often made constant reference to the 1963 essay "Seeing and Using: Art and Craftsmanship" by Mexican poet and writer Octavio Paz. More importantly, she broadened her horizons on craft through collaborations and exchanges with potters from around the world.

3. 1958-1978: Teaching at Macdonald College

Namer was recognized across Canada as an exceptional, rigorous, and devoted teacher and mentor. She played a key role in the establishment of studio ceramic education in Canada through her work as head of the ceramics department of McGill University’s MacDonald College. She began teaching in 1958 while still a student at Montreal's Institute of Applied Arts. She was first approached by a local pottery club, The Claycrafter, to teach afternoon workshops at Macdonald College. She initially intended to teach there for only two years but was then hired as head of the ceramics department, a position she would occupy for eighteen years. Before her arrival, the department had been closed for twenty-five years, requiring Namer to work considerably to modernize and restore the outdated equipment. She built the department's kiln herself and put in place a fully equipped studio that allowed her to instruct up to eighty-five students a week (Wells, 1966).

Namer working in the MacDonald College pottery studio, circa 1965.

The quality of instruction in Namer's department rapidly gained a reputation in Montreal's craft community. Her course attracted a diversity of students: "business and professional men," as well as "professional women, housewives, and society matrons" (Rochester, 1963). Moreover, Namer taught university students and teachers-in-training. Many of her students, such as Brenda Sullivan, Joanne Cunnington, Phyllis Atkinson, and Eileen Reed, became influential contributors to the field of studio ceramics in Canada. Ceramics was taught in her class as a profession and not solely as vocational therapy. Notably, Sullivan describes how Namer "taught [her] to study as a professional potter, not as a hobbyist," and "instilled a particularly strong work ethic." Under Namer, "serious education was possible;" Namer's courses were considered "the only suitable [ones] in Montreal for those interested in becoming professionals"(Crawford, 2005).

Her students received a thorough education. They would learn to prepare clay in its raw form and were encouraged to experiment with various materials sourced across Canada. They would also learn about the use and maintenance of technologies and equipment. One of her courses taught students how to build kilns. In this way, Namer would encourage students to establish their own independent pottery studios. She also offered more advanced classes where students could deepen their knowledge of glazing techniques and technologies. As opposed to most of the ceramics departments in the country, students learned to prepare glazing recipes instead of using commercially prepared ones (Rochester, 1963).

Namer's mentoring was not limited to Macdonald college. She shared her expertise in a series of seminars organized by the Montreal Potters' Club in the 1960s. Furthermore, she lectured at the Institute of Applied Arts for two years. She also led numerous workshops and worked as a consultant for independent ceramic studios across the country. Notably, she oversaw the construction of the kiln for the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and its ceramics studio at the end of the 1960s. She was invited by the new president Garry Kennedy "to lead the clay section (..) as a stoneware specialist," an offer that Namer declined because she felt the need, at this moment in her career, to refocus on her personal production: "I gave so much energy to teaching. The ideal way is to teach when you are old and tired, not when you are just starting out" (Crawford, 2005).

4. The 1960s: Emergence as a Professional Potter

The 1960s marked an epoch of intense and focused production in which Namer forged her identity and reputation as a craft professional. In parallel to teaching full-time at Macdonald College, Namer responded to a growing number of orders, sometimes producing “at least 300 hundred domestic articles every week.” To combine her teaching career and studio practice, she followed a demanding schedule. In her personal studio in the basement of her home, she shaped and prepared ceramics pieces and then brought them to Macdonald College for the firing and glazing using the department’s equipment before her classes began (Crawford, 2005).

Starting early in the morning and finishing late at night, "she was totally consumed by the world of pottery-making" (Crawford, 2005). For Namer, "If you are a producing potter instead of a past-time potter, you [need to] build your life around it." She also expressed how the nature of the medium demanded that it become "a way of life": "You can't start some pieces and then run off for a holiday in the country." Gaetan Beaudin described Namer as “the hardest worker he ever knew” while Gail Crawford characterized her as a “high powered intense woman” (Crawford, 2005).

Namer started participating in numerous national craft exhibitions at the beginning of the 1960s. Her work stood out for her skillful use of the material and her mastery of glazing. In 1962, her Toronto's Galerie Artisans mounted Namer’s first solo exhibition. The same year, she participated in the 22nd Ceramic National exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York. This first exhibition in the United States allowed her work to gain international attention. She then participated in craft exhibitions in Berlin, Germany and Faenza, Italy. In 1963, she won the first prize of the Association Professionelle des Artisans du Québec for her work presented at the 8th Edition of the Palais du Commerce’s Craft Fair. Seeing her pottery, MacLean's journalist Gilles Derome described Rosalie Namer as "one of the most solid potters in Canada" (Derome, 1964). This recognition launched her career and marked the beginning of her professional success.

In 1965, she acted as the chairman of the jury for the Biennale of Canadian Ceramic, where she and colleagues Robert Champagne and Yves Trudeau established the biennale's selection criteria and publicly discussed what they considered to be the direction of contemporary pottery. This experience consolidated her status as a leading figure in the Canadian field of studio ceramics.

Following these exhibitions and appearances, Namer received a growing number of commercial orders. While at the beginning of the 1960s she sold her work mostly to clients and galleries from eastern Canada, by the end of the 1960s, orders were placed from across the country; "[her] work [was] all spoken for." During this productive period, Namer worked swiftly and had one of Canada's most abundant and regular studio productions.

5. 1968-1969: Experimentations and Research

Namer was awarded a grant of $6,000 from the Canada Council for the Arts in 1968 with the purpose of conducting extensive experiments on Canadian clays. Up until that time, Namer worked with a sandstone sourced in Saskatchewan, but this clay became unavailable, and Namer needed to find a new supplier. A similar type of clay could be purchased in the United States, but Namer preferred to source her material in Canada. Indeed, through her craft, she wished to call attention to the rich clays of the Canadian landscape. Furthermore, she was not satisfied with the clays that available on the market and wanted to develop better options for Canadian potters. On the one hand, her research project responded to the need to source suitable and affordable clays in local deposits; on the other, it was fueled by a desire to experiment with new materials and to renew her craftsmanship. With this funding, Namer traveled to different clay deposits in the Canadian prairies and the Maritimes. She was particularly interested in white stoneware sourced from the Shubenacadie area of Nova Scotia and established a commercial relationship directly with the clay deposit.

She would present the outcomes of this research in two major Canadian craft exhibitions, Ceramique 69 and Dimension Canada, and, in a solo show at Montreal's Central d'Artisanat. Furthermore, in 1970, she was awarded the Grand Prix d’Artisanat du Quebec in recognition of her experimentations with Canadian clays. These three major exhibitions and this award marked the end of a prolific decade of production and experimentation and sealed her reputation as one of the strongest potters in Canada.

Solo exhibition at the Central d'Artisanat, Montreal, 1970

Solo exhibition at the Central d'Artisanat, Montreal, 1970In 1968 and 1969, in parallel to her project on Canadian clays, Namer also conducted an independent scientific investigation on lead glazes in collaboration with Dr. Ben Warkentin, professor of soil analysis at MacDonald College. Namer undertook this project after a child in Montreal died from lead poisoning: the young boy had drunk juice from an earthenware pot handcrafted by an amateur potter in Nova Scotia. When in contact with the juice's acidity, the container's glaze released soluble lead, which caused the fatal intoxication. Namer tested a series of twenty handcrafted and commercial pots that she suspected could represent public health hazards. She also reproduced common glazing recipes that used lead and experimented with their firing to analyze how their composition changed. She presented the results of her experimentations in an article entitled "Earthenware Containers as a Source of Fatal Lead Poisoning," co-written with Dr. Michael Klein, Eleanor Harpur, and Richard Corbin, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1970. Namer suggested a series of recommendations: the government needed to impose on craftspeople guidelines to ensure that all pots were safe for table use. She further recommended that only professionally trained potters with a good understanding of the chemistry of clay should be allowed to craft objects for table use and that pre-mixed glazes should be compulsory for beginners and amateurs. This research highlighted the scientific aspect of Namer’s career; she was recognized not only as a potter but also as an expert in glaze chemistry.

6. 1970s: Work at the Beaconsfield Studio

After her research in Nova Scotia and her scientific investigation into lead poisoning at the end of the 1960s, Namer felt she was spending too much time away from her wheel. The 1970s therefore mark a return to the studio and represent a period of maturity and prosperity for Namer. Her career was established, and her previous shows' success allowed her to secure clients and orders across Canada. For these reasons, she stopped participating in competitions and exhibitions to focus on what was most important to her: producing functional objects for the public.

Namer photographed by Richmond Jones in her Beaconsfield studio.

She built a studio in her home on the West Island of Montreal. Large windows, old wood furniture, and various plants transformed the pottery studio into an organic environment (Morency, 1970). The completely furnished workshop was equipped with a manual wheel and a large kiln "that can reach 200 degrees and receive up to 250 middle-size ceramic pieces." There was also a room where Namer prepared the clay and space for mixing and applying the glazes. This installation allowed her to produce hundreds of pieces per week.

7. Final Years

In 1978, at the age of 52, Namer suffered a spinal disc herniation that would forever alter the course of her life and work. The making of pottery is an intensely physical activity that over the long term has an impact on the potter's body. Namer worked daily with a manual kick wheel for over twenty years, an activity that involved persistent, repetitive movement, potentially creating the conditions for what became a sustained back injury. Numerous surgeries followed, one which led to the accidental puncturing of the cerebrospinal fluid sac surrounding her spinal cord, causing metastasizing inflammation of the fluid sac. In consequence, Namer developed arachnoiditis, a permanent, untreatable disorder which causes chronic and persistent pain, numbness, tingling, stinging and burning sensations along the spinal cord. After a series of unsuccessful surgeries in the 1980s that failed to relieve Namer’s pain, her physical condition made a return to the pottery studio impossible. This represented a dramatic turn of events that forced Namer to abandon a practice and passion that had been integral to her life for more than two decades.

Namer sold her pottery studio equipment and began experimenting with other forms of creative expression and mediums more adapted to her physical condition. She notably bought photography and print-making equipment. However, her chronic pain, more than a physical disability, deeply impacted her ability to create and develop a new artistic practice with these mediums.

Polaroid self-portrait with aubergines, azaleas, and ficus, Beaconsfield, circa 1985.

Polaroid self-portrait with aubergines, azaleas, and ficus, Beaconsfield, circa 1985.In 2006, after almost three decades of unsuccessful chronic pain management, Rosalie Namer travelled to Zurich, Switzerland, to seek physician-assisted suicide facilitated by the Swiss non-profit organisation Dignitas. She died on May 10, 2006, accompanied by members of her family.

Research

Jeanne Blackburn, with contributions by August Klintberg, Michael Namer, and Benny Nemer. Last update, July 19, 2025.

Sources & References

Gail Crawford, Studio Ceramics in Canada, 1920-2005. Gardiner Museum, Toronto; Goose Lane Editions, Fredericton, 2005

Gilles Derome, "Artisanat : Du Miel et du Vinaigre," Maclean’s Magazine, March 1964.

Serge Fisette, Potiers Québécois. Les Arts Du Québec. Montréal: Leméac, 1974

Michael Klein, Rosalie Namer, Eleanor Harpur, Richard Corbin, "Earthenware Containers as a Source of Fatal Lead Poisoning," The New England Journal of Medicine, September 24, 1970.

Bernard Leach, A Potter's Book. 2d ed. London: Transatlantic Arts, 1945.

Mireille Morency, “Rosalie Namer, céramiste : ‘J’essaie de faire des choses belles mais fonctionnelles’,” Québec-Press, Montreal, July 1970.

Octavio Paz, "Seeing and Using: Art and craftsmanship." In Convergences : Essays on Art and Literature, San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987.

“Rosalie Namer: First Grant: 1978, 6000$” The Financial Post Magazine, May 1978.

Helen Rochester, “College Pottery Courses Attract Many”, The Montreal Star, February 2, 1963.

Lana Wells, “Pottery is Woman’s Hobby, Job”, The Gazette, April, 1, 1966.

Photograph

Uncredited portrait of Rosalie Namer in the teaching studio, MacDonald College, Montreal, circa 1965.